Rond de jambe (2015-2016)

Video installation and live-performance

Rond de Jambe is a research project that takes the history of the Stopera building in Amsterdam as a starting point. Built between 1979 and 1986, the building that serves as a home for the National Opera and Ballet as well as the City Hall was created with strong opposition from the neighbours and left-wing movements in Amsterdam.

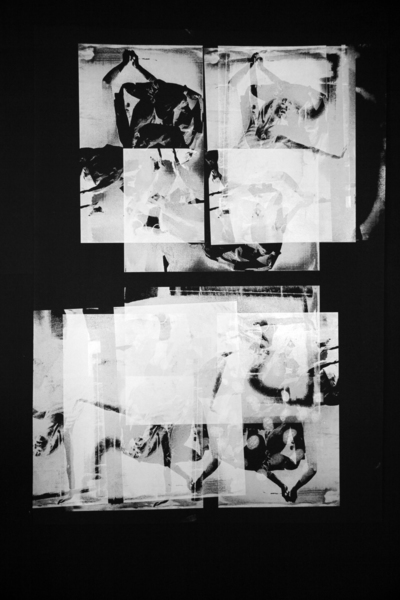

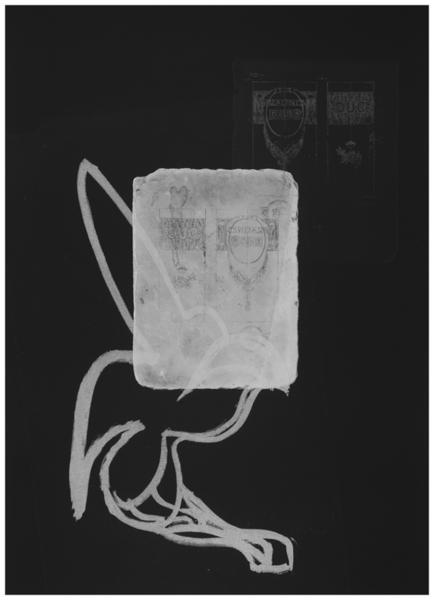

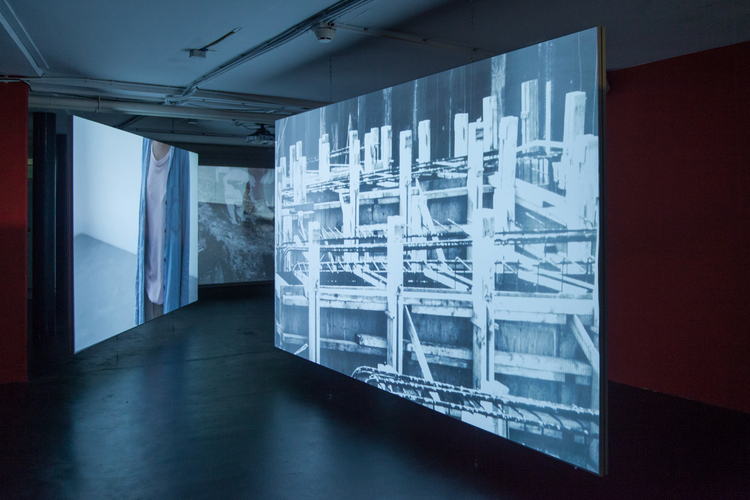

installation view at 2 Unlimited, De Appel, Amsterdam in 2018 Photo: Konstantin Guz

installation view at 2 Unlimited, De Appel, Amsterdam in 2018 Photo: Konstantin Guz

They claimed, among other things, that the space should be used for social purposes and houses, in opposition to that, the Stopera building would serve to an elite, and had been planned without any historical and social awareness or perspective, nor dealing with the traumatic history of the area (the old Jewish area) which was marked by the WWII.

The conflict between the city government which supported the Stopera building and the neighbours led to years of confrontations, protests and demonstrations.

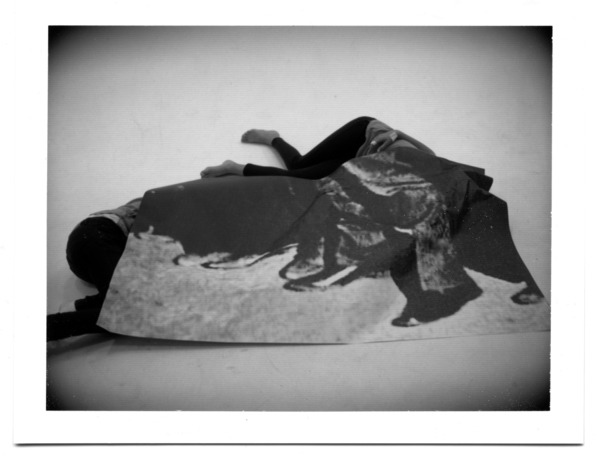

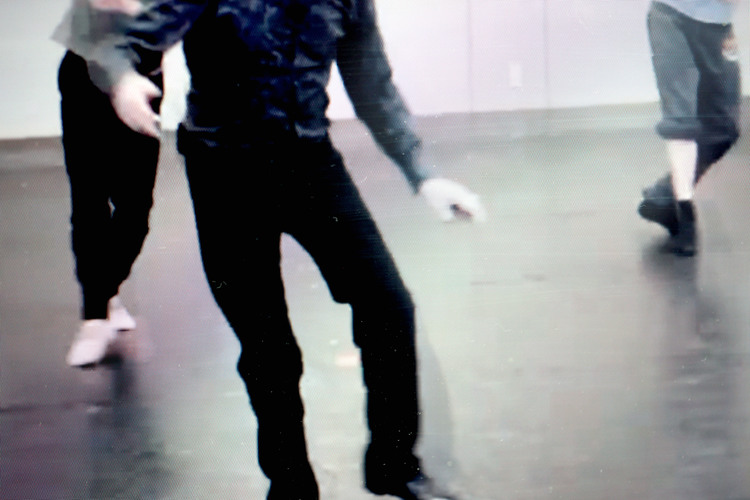

Exhibition view, L'Art de la Revolte, Centre Pompidou Paris, 2016.

The work Rond de Jambe takes this history as starting point and juxtaposes the 'political body' and the 'dancing body', by using archival images from these demonstrations and protests, and working together with dancers, translating the movements into dance.

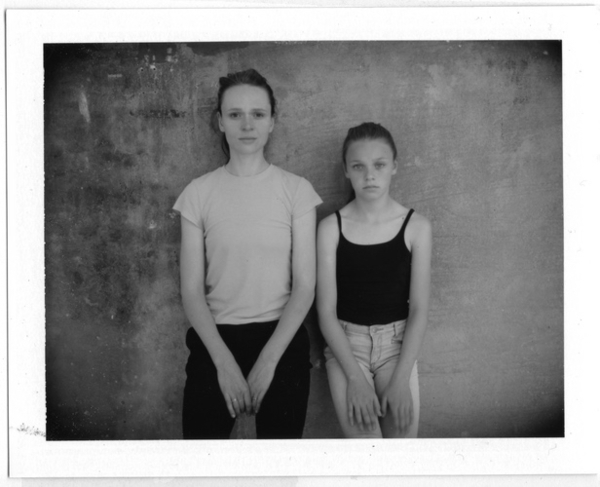

Photo by Hans Bouton (source: Internet)

Installationview @ Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam Photo: Sander van Wettum

Rond de Jambe. Notes to join movement

Life itself was one of the causes deeply embraced by the twentieth century. Once the fall of humanist paradigms from previous centuries had been confirmed, together with the triumph of bio-politics, the twentieth century dedicated itself to inventing radically new ways of life: utopian communities, avant-garde groups, revolutionary movements.

One of the most fundamental questions that surfaced from the echo of this collapse was posed by Walter Benjamin: how can art imagine that which overcomes from nothing? Or we could otherwise formulate: how may art generate the necessary movement that takes quiet and mute bodies out of their repose? Has the body something to say in this respect?

Well, the human body is a physical object with sensitive properties. One supposes that the body has a determined extension and, moreover, its own strength. The human body is, specifically, the organic material that constitutes a human being.

What potential the body has, nobody knows. Or maybe yes? Maybe the body itself knows?

If we consider the body from the opposite perspective of bio-politics, as a body- agent or a body-subject, then we might stop thinking the body as a political tool. If the body works as a tool, and a tool is something used for something, then we are forced to think: for what is the body used? And then, through the art of circular thoughts, we find ourselves once again with a body-object. The body is the difference, and the difference is what allows change to come in. Change is also movement, although we are used to think that only movement generates change.

And now one body, many moving bodies. Have you already thought about what a Rond de Jambe is?

Which breakdowns should the twenty first century contemplate? Maybe that of the body? But if the body is capable of recovering the human capacity for experience, merging individual memory with collective memory, then let us put it into movement.

*Camila Zito Lema (ARG/1988) is a philosopher based in Buenos Aires.

(Original Spanish version)

Rond de jambe. Notas para acompañar el movimiento

Una de las causas que el siglo XX abrazó con fervor, tuvo a la vida como protagonista. Una vez constatado el derrumbe de los paradigmas humanistas de siglos anteriores, a la vez que el triunfo de la biopolítica, el siglo XX se dedicó a inventar formas de vida radicalmente nuevas: comunidades utópicas, grupos de vanguardia, movimientos revolucionarios.

Alguna de las preguntas fundamentales que surgieron como eco de ese derrumbe fue formulada agudamente por Walter Benjamin.¿Cómo el arte puede imaginar aquello que sobreviene a la nada? Nosotros diremos, ¿cómo el arte puede generar el movimiento que saca del reposo a los cuerpos quietos, a los cuerpos mudos, -en la estela benjaminiana- de experiencia comunicable? ¿Acaso el cuerpo tiene algo que decir?

Ahora bien, un cuerpo es un objeto físico que posee propiedades sensibles. Se supone que un cuerpo tiene una determinada extensión. Además, todo cuerpo tiene una fuerza propia. Específicamente, el cuerpo humano es la materia orgánica que constituye el hombre.

Lo que puede un cuerpo, nadie lo sabe. ¿O si? ¿Tal vez lo sabe el propio cuerpo?

Si pensamos al cuerpo, desde las antípodas de la biopolítica, como un cuerpo agente, un cuerpo sujeto, entonces tal vez deberíamos dejar de pensar al cuerpo "como herramienta política". Porque si el cuerpo es como una herramienta y la herramienta es algo que se usa para algo, estamos obligados a plantearnos ¿para qué se usa el cuerpo? Y ahí, por arte de los círculos del pensamiento, volvemos a tener un cuerpo objeto. El cuerpo es la diferencia y la diferencia permite la entrada del cambio. El cambio también es movimiento, aunque estemos acostumbrados a pensar unilaterlmente que solo los movimientos generan un cambio.

Y ahora un cuerpo, muchos cuerpos en movimiento. ¿Ya pensaste qué es un Rond de jambe?

¿Y qué derrumbes son los que deberá pensar el s. XXI? ¿Acaso el del propio cuerpo? Pero si el cuerpo es capaz de recuperar la capacidad humana de la experiencia, ensamblando la memoria individual con la memoria colectiva, pongamoslo en movimiento.

Camila Zito Lema, Buenos Aires, 2015